Looking for Moby-Dick in Paris

The White Whale had been ubiquitous in my life long before I first set sight on It.

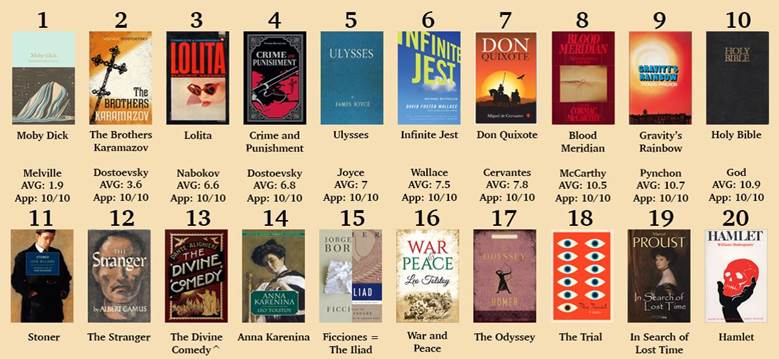

If my grandfather’s focus was more on ancient Greek, latin, francophone and romance languages literature, he did transmit an absolute reverence for “the classics”. Aesop and Homer, both Pliny, Balzac, Hugo, Cervantes and Dante were his pantheon, and some of their works entered mine, in due time.

My own literary journey bifurcated early on, as I was more drawn towards the anglophone literary sphere and its giants, leading me early on to Shakespeare, Huxley, London, Nabokov, Wallace, and others, and yet there was, looming into the distance, a marble behemoth I had anxiously overlooked for about 15 years. Praised to the Heavens was this novel, a work whispered of in hushed tones reserved for Dante’s inferno, Don Quixote, the Bible, one that, year after year, topped the chart on my chosen field to discuss literature (before you judge me, /lit/ was vastly different in 2004). Here’s an aggregated list of the last two decades of that chart, to get but a taste of my formative idea of “the classics”.

There it was, oft perched atop this list, nary below number 3 out of a 100 out of millions of novels. I had heard it exalted by Harold Bloom, and virtually every other author listing it as crucial developmental reading, nay, experience. It had been read to David Foster Wallace from the age of 6. Simply a work an afficionado couldn’t pass up on, its place in literary history cemented beyond any shade of doubt.

And yet, it took me 27 years to get to finally set sail on my reading of the divine beast, as I was probably anticipatorily terrified of its cachet, its influence, of a shattered self should I fail to fully grasp its majestic beauty.

It was love at first read.

Love ascended to monomania for some six months, as I was breezing through a late, accelerated bachelor’s in English Studies in Lyon, France. I had all the time in the world to get lost in the high seas of this paragon of literature, and I devoured all I could get my hands on that was tied to the White Whale. Youtube lectures galore, secondary literature aplenty, but also many other mediums, from Huston’s 1956 movie, to countless artistic interpretations (special shoutout to Cosimo Miorelli’s Loomings collaboration with ArtonWords.com, its framed print centerpiece of my last three living rooms), to the MobyDickBigRead audiobook project of my creative writing professor Phillip Hoare during my Erasmus year in Southampton (an overnight reading of his Risingtidefallingstar book on the glass-ensconced patio of my shared house in Southampton during a storm, one invaluable highlight of my journey). Another conference by Francois Sarano (oceanographer, diver and researcher of captain Jacques Cousteau) at the Musée des Confluences in Lyon, in 2019, will deserve its own recollection another time.

The obsession eventually abated, not greatly, but never again to quite reach the single-mindedness of those years.

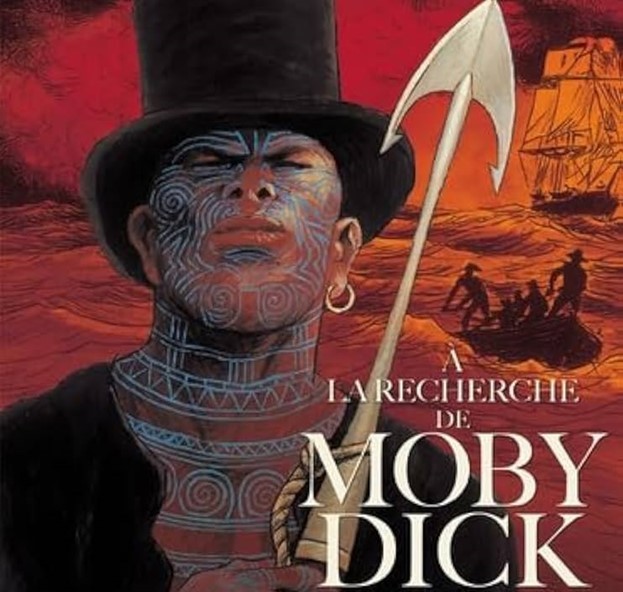

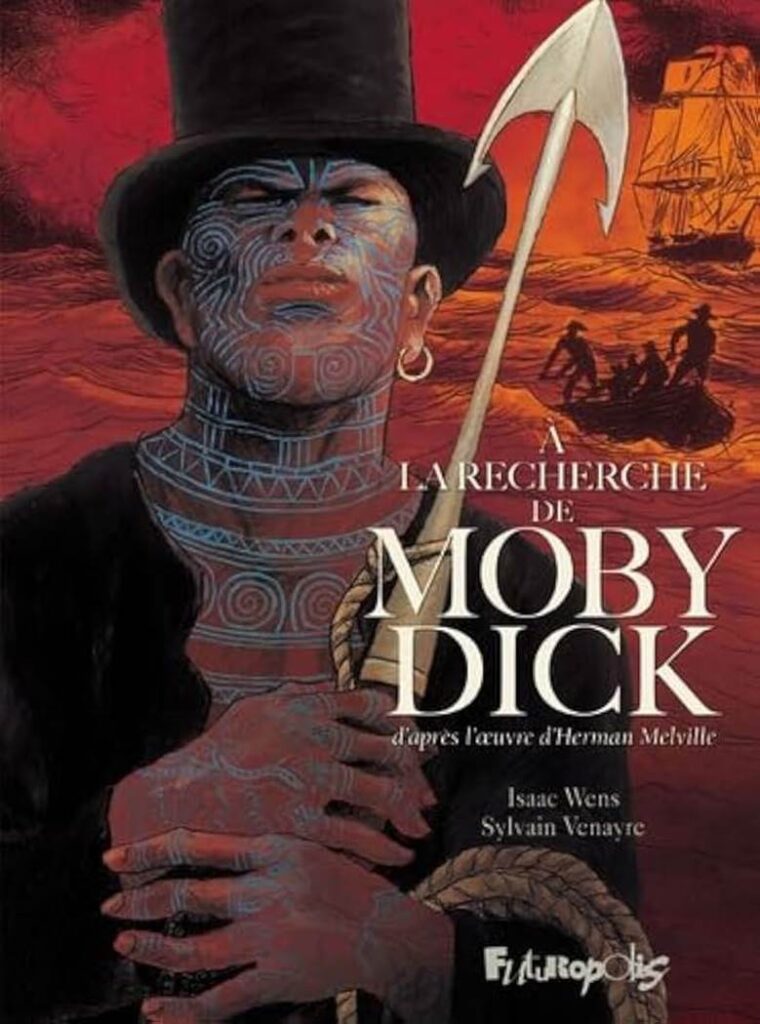

That period is about 5 years removed from the typing of this review, (yes, this is a review, I am getting to it, sorry for that silly “life story in a recipe digression” business, dear reader, please bear with me for a short while longer) and, while the monomania calmed down, the love and fascination never went anywhere. During my bi-yearly peregrinations back to my homeland of France, I never fail to peruse comic book stores, one way for me to keep in touch with the culture of my country of origin. Last year that store in Paris greeted me with this 2019 adaptation of Melville, titled Looking for Moby Dick. On the cover stands an inscrutable Queequeg, harpoon in tattooed hands on a background of a murderous orange and dark red sea.

It was enough for me, as I am a simple man when it comes to Moby-Dick and bande dessinées. Luckily for me, there aren’t too many temptations testing my reluctant consumerism, this weakness of mine being a rather niche intersection. Just don’t tell my algorithm, ok?[1]

This is the review of that book.

Adapting Moby-Dick is a task both herculean and quixotic, a quest, ironically enough, thousands of artists have embarked on, as the novel has inspired legions, to the point of obsession, of rabid, all-encompassing devotion rarely reached by other novels. On that 4chan top100 list, only a very select few can claim to a similar degree of worship: infamous Lolita, glorious Ulysses, intrepid Don Quixote, and potentially the other novel with a giant white albino for antagonist: Blood Meridian. Yet, I’d wager, none of those have led to a fraction of the various Moby-Dick adaptations we have today. Maybe the Bible, if one must concede. After all, one could easily argue Moby-Dick itself to be an adaptation of the Bible and its story of Jonah, so deep does Melville’s ocean of references to the good book runs. But this would be a debate for another stage.

While many have attempted to adapt Moby-Dick through different mediums, few can be argued to have qualitatively succeeded. This French comic book, scenario by Sylvain Venayre, drawings by Isaac Wens, may very well be in the latter rather than the former, for reasons I shall get into down below, but even beyond those considerations, the very meta question of adapting such a sprawling, all-encompassing, philosophical epic novel, is at the core of this comic book, as illustrated by a subplot masterfully connecting pages directly adapting the plot of Moby-Dick.

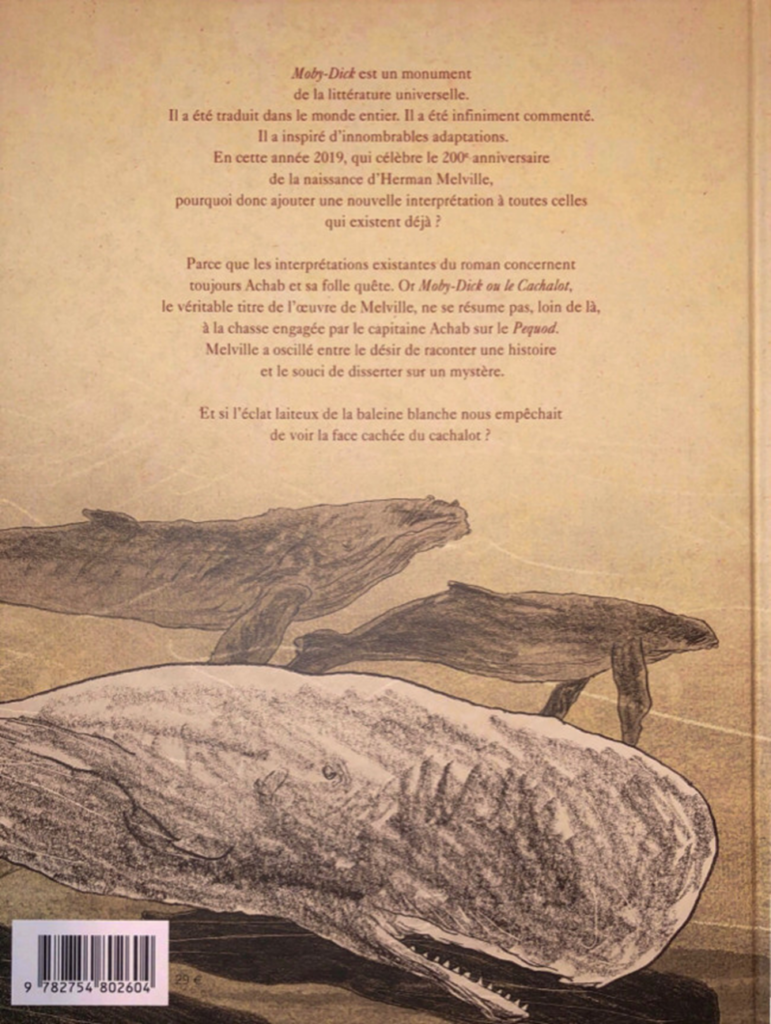

The preface to this book is a message by the writer Sylvain Venayre titled “La face cachée du cachalot” (“the sperm whale’s hidden face”) with an illustration of four different whale species (one mirrored on the back cover of the book). This primacy given to whales is very deliberately echoing Melville’s own little-commented prefacing of the story of Moby-Dick with a compendium of literary quotes discussing whales and sperm whales from eminent works and authors.

Indeed, in this preface, Venayre deplores the lack of focus in academia and the arts around the whale question in Moby-Dick, instead focusing on Ahab’s mad quest, Ishmael’s narration, or the rest of the Pequod’s inhabitants. The author, while not eschewing this part of the tale, uncovers his aim to give his own Moby-Dick, a broader approach, one that modern readers might be drawn to, in an age of feminism, where the scant mention of women throughout the whole novel cannot be solely justified by their historically accurate spatial exclusion aboard whaling ships, bar rare exceptions for captains’ wives, but also, a narrative that ought to be revisited post 1986 and the International Whaling Community’s moratorium, and the general hindsight on commercial hunting and species extinction, since Moby-Dick’s publication in 1851, and a Melville who would have been unable to ignore the dire fate encountered by buffalos, whales, and countless other species during his time.

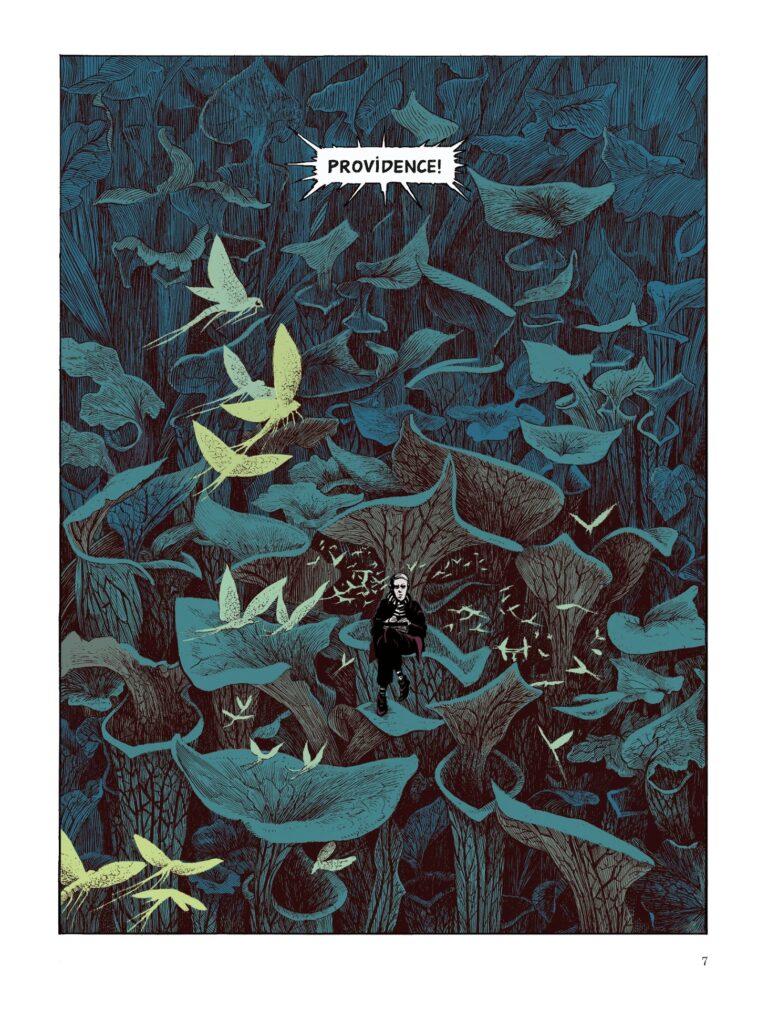

Past this preface, Recherche (as I will heretofore refer to the French comic book in question) already show its true colors, opening not with Loomings, its “damp, drizzly November in my soul”, not even, which might be blasphemy in any adaptation of the original, the most iconic “Call me Ishmael”, but rather with the “Town-Ho’s Story”, aka chapter 54 in the novel.

This choice, however, might prove truer to the reality of Moby-Dick than Moby-Dick itself, as a month before the November 1851 publication of Moby-Dick, The Town-Ho’s Story was published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, effectively opening the book to a larger audience. While this common marketing ploy largely failed to whet reader’s appetite (given the book’s commercial failure), Melville’s decision to use that chapter makes sense, as it introduces a lot of themes present in Moby-Dick, as well as some portentous insight as to Ishmael’s fate and personality. This chapter, ultimately placed toward the later part of the first half of Moby-Dick, serves as another long-winded (indeed, with 7938 words it stands as the longest chapter out of its 135 total) “digression” from the main plot, and makes a rather fitting introduction to Recherche.

After “Town-Ho”, Recherche directly moves to “The Embarkment”, preserving Moby-Dick’s cut into chapters (a somewhat unusual convention in comic books and “bande dessinées”), albeit adapting it to only 5 in total, from the 135 of the original. If it weren’t clear quite yet, this is neither a direct nor a strict adaptation.

“Embarkment” covers quite a lot of ground, and it isn’t until the end of Ahab’s passionate speech in “The Quarter-Deck”, chapter 36, and his “Death to Moby-Dick” plea, that the following chapter “The Sphinx” is announced.

As mentioned previously, “Embarkment” doesn’t open with a depressed Ishmael looking to dispel his existential dread, but rather with a shot of a blue Parisian sky, a microphone, a coffee cup, and the celebrated first Moby-Dick line “Like an orange?”. New England will have to wait a couple of pages, for this sets up the core of what Recherche is about. Research.

Here, a young radio host, looking the splitting image of the Ishmael we shall meet two pages later, inquires about the puzzling statement made by a passionate white-haired, white-bearded, blue-eyed man (physically indistinguishable from the Ahab we have yet to meet) we will later uncover as a theatre director who “failed” to bring Moby-Dick to the stage. For now, he likens Moby-Dick (the whale) to an orange. This is all I shall say on the matter, as I attempt to whet your own appetite for Recherche, feeding you the orange whole would cause you a great disservice, dear reader, if it were to render your upcoming first reading somewhat superfluous. Despite my best efforts, I’d argue that this review, and even more so the sections to follow, will take away from your own first experience. Maybe don’t abandon all hope, but certainly beware, ye who enter here!

As our director connects Moby-Dick to an orange, he introduces Ishmael as the character Melville needs to research the whale, hunt the whale and thus, get to know the whale. Ishmael had to be both hunter and researcher, philosopher even, to even aspire to know the Whale. As the panels transition abruptly from a Parisian apartment to Ishmael and a New England winter, the narration stays with the director for a couple pages before turning to a straight adaptation of the Moby-Dick plot. At least for a few pages. As Ishmael is shown to his room at the Spouter-Inn, the story abruptly cuts to a whale skeleton in a museum, and our interviewed director pontificating about Baron Cuvier, the French zoologist, but mostly about whales and their scientific classification. This is the “Cetology” chapter, as adapted in Recherche, and is illustrative of the comics’ approach to this adaptation: following the main threads of the original plot, with intertwined chapters about the research interview, standing in for the countless “digression” chapters in Moby-Dick.

To me, this is what makes Recherche a resounding success. Adapting any novel to a different medium comes with its mountain of challenges, let alone The Great American Novel that is Moby-Dick, replete with philosophical reflections, literary references, biblical and Shakespearean mostly, infamous “dry” biological information, even “dryer” (I humble disagree with the common assessment, hence the quotation marks) nautical terminology.

As much an afficionado as I am of the cetology chapters, or any “digression” from the plot in Moby-Dick, they are very much where the main challenge lays when it comes to adaptation. Barren of them, the novel loses its literary luster, turns into a relatively “simple” or at least, far more straightforward adventure story. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Yet, I would argue, the beauty of Melville’s creation requires the awe and wonder generated by the overabundance of “digressions” to truly shine. Without Ishmael’s erudition, Ahab’s ramblings turn paltry, his quest, as Starbuck argues, mere “vengeance on a dumb brute”.

However, those chapters, precariously engaging enough in the novel, would easily prove an utter bore in a more visual medium, with different, faster-paced expectations. The adaptation’s challenge is to preserve, to nurture the “other” quest in Moby-Dick, inseparable companion to Ahab’s monomaniacal machination, and inject the spirit of those “digressions” into the newly formed narrative, in a way that fits the different medium and doesn’t chance losing its audience.

In Recherche, it takes the shape of that interview. Far from a static setting, the interviewer and interviewee traipse around Paris, linger on the director’s stage, visit a professor, another artist. It makes great use of what Scott McCloud calls “the gutter” in his 1993 book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. The shift between an almost “straight” adaptation of the original plot to the interview is done seamlessly, can be at times rather abrupt, and leaves the reader free to fill in gaps both aboard the Pequod, but also in the two men’s journey across Paris. The “gutter” (one could also use Will Eisner’s terser “interpanel space” if the negative gutter connotations seem too off-putting) here is a vast, engaging network spanning oceans, continents, both time and space. There isn’t much to indicate the passage of time in either narrative: the interview could very well have spanned one full day, with many stops, but could also have fitted several meetings, given the breadth of the conversation, the museums and monuments the two men visit, mobilizing over fifteen members of the cast to act some passages of a play never to open, taking time out of the busy schedule of the artist friend and Sorbonne university professor. There is the use of “closure”, again, a McCloud term of inference: if the upper panel on page 55 shows the two men walking around a metro entrance, in the following panel they are walking alongside a smaller street around what looks to be Châtelet–Les Halles, before following the Seine up to the Colonne Vendôme where Napoleon stands vigil atop his 44-meter bronze mast. This journey takes about 20 panels, which Parisian readers could easily follow in their mind map or google maps for the less analog among them.[2]

Similarly, time aboard the Pequod eschews linearity, all the more so in the panels of Recherche, with a frequently interrupted narrative and no dates to anchor our understanding. The reader’s collaboration in filling gaps is fully engaged, as the crew jumps from lunch to frantic activity to Ahab’s pondering and Flask gossiping unceremoniously after each interruption of varying length.

What helps these frequent shifts between two narratives is their blending together by two crucial factors. One, as previously mentioned, the young interviewer is, in face, physique, and even style, indistinguishable from Ishmael, and the director a carbon copy of Ahab. In the director’s case, the similarity is intended. He strives to stage Moby-Dick and has cast himself as Ahab. On stage, he slathers red paint over his eye, mirroring the captain’s scar, before launching on a dark monologue.

Secondly, the importance of the play within the interview narrative cannot be understated. The preface already states that the author considered adapting Moby-Dick to the stage before the comic book, which birthed the director character, as the original work already sets that stage, Melville’s theatrical indications fully appear in chapter 40 “Midnight, Forecastle”, as well as a dramatic tone pervading the novel. Here the director is presented as a “failed” Ahab, one who renounced on his White Whale after realizing the futility of his quest, most quixotic of all, to encompass the infinity of that most bounteous of novels on a most finite stage.

The line is thus blurred between Moby-Dick and Recherche, interview and original plot, Ishmael and interviewer, both researchers hungry for knowledge and experience, between Ahab and director, mad for their vision, equal in their obsession, yet ultimately divergent in their dedication, in the outcome of their folly.

As the two men, alongside the large cast, are shown on the stage where the director failed to set up his play (actors in costume, largely in character as we are introduced to Bulkington, Starbuck, Pip and Queequeg). The director evades questions about his failure, the renouncing of his quest, at a rather advanced stage (costume and set are ready, crew is cast, the attempt must have been genuine), and humanizes failure, qualifying Ahab’s quest as, well, a failure also, “A rather beautiful failure, was it not?”.

I will spare you more detail on the Pequod part of the comic book. The adaptation is faithful, few crucial scenes are omitted, which, in itself, is quite a feat for this 220 pages volume, of which maybe 30% is dedicated to the interview part. Too approximate? Fair. In the spirit of Melville and his tediously extensive scientific recounting of whales, I shall aim for more clarity and accuracy. 5 pages of preface, 139 pages to 62 in favor of plot over interview. Two to one. 28.2%. Not to pat myself on the back too much, but my intuition was pretty much flawless!

Anyhow. Where the interview takes us is what is more interesting in this adaptation. For all its talk about giving the focus back to whales, there is nary a mention of them past the initial natural sciences museum section of the interview (loosely corresponding to the cetology chapters) and a mention of their classification, hunting, and extinction. The second museum is more ethnology and anthropology, and there they discuss phrenology, scientific racism at the time of Melville and his rejection of it (“Melville says the shape of Queequeg’s skull reminds him of Washington’s busts”).

The next section is the Sorbonne, where a professor expounds on names and their significance, on biblical references, or at least on the major ones: the Pequod (“A ship serving a quest of knowledge and signifying the death of the Other.”), Acushnet (on which Melville sails on his first whaling voyage, another extinct Indian tribe), Adam and Eve, the tower of Babel, Bildad (the “old friend”), Peleg (“division”), Ahab and Ishmael, but also on history and numbers, religion, especially Queequeg’s fasting (qualified as “Ramadan” out of convenience by Ishmael and Melville, even if Queequeg has nothing to do with the Muslim practice).

I have already briefly mentioned the leisure walk to Napoleon’s resting mast. There are few mentions in Recherche of both Melville’s ties to Paris (“At the end of 1849, a few weeks before starting to write Moby-Dick, Melville was in Paris, admiring the Victory Column, visiting the Cluny Museum that had just opened.”), and of the famed novel in French literary culture. A good part of the “interview” chapters turns philosophical, as our director becomes more and more animated, directly mirroring Ahab in the subsequent plot sections.

I have yet to talk about the artwork in Recherche. Personally, the style isn’t exactly my cup of tea. Rough crayon coloring has its charms, especially compared to glossier, more uniform digitally assisted coloring, and does serve Ahab’s intensity of will, yet it doesn’t move me, especially in the more peaceful interview chapters, that could stand more delicate precision. But this is nit-picking. The overall effect stays potent and grew on me after a few readings. Its roughness also provides a striking contrast to my favorite chapter, both in the original and Recherche: chapter 42, The Whiteness of the Whale. In the comic book, the director told his interviewer they were going to visit one of his artist friends, and after a short plot interlude, we (readers) turn the page to a whole expanse of white only severed by a 0.5x2cm rectangle with “La blancheur” (“Whiteness”) written in it. There, for 10 pages, one-sixth of the total interview chapters, a bald artist presents the ideas of the original chapter in many varied styles, in, to me, what is the highlight of the book, and justifies it almost outright. This is what the original chapter strove to be, taking full advantage of its medium, the written word, to enact an effect so potent it shaped my own appreciation of art and parallels with life. The Recherche interpretation matches that effect majestically, taking full rein of its own different medium and undeniably doing it justice.

By the end of the comic book, one of the very last interview chapters has a similar stylistic aspiration, it starts off as a mention of the Doubloon chapter and veers into an admission from the director of his reasoning as to his failure to adapt the novel to a stage it was almost promised to. There our director/Ahab appear transcendental, translucent, over a shining sea of golden hues, he stands gigantic, God-like, the crayon coloring even rougher in its frantic strokes. The comic book is reaching its apex, as the Chase begins in the plot section, and is delivering every promise of adventurous Fate.

The interview section ends at page 183 out of 220, leaving a lot of space for an unadulterated Chase. That last solitary page is not the preliminary interview any longer, but our two men at the radio studio, concluding the actual show with the director admitting the abandoning of his quest, yet enjoining others to attempt it, not because they may succeed where he failed, given how implausible the task seems, but because, like great novels, great works of Art, Moby-Dick helps us to get to know ourselves.

I have already said too much. The fury and silence, at the end of the Chase, especially the sight of the three harpooners sinking motionlessly on each of the three masts (no last futile attempt to nail a flag to the mast, Queequeg remains regal to his last resigned breath), left a mark on me.

As I hope to have convinced you, dear reader, please read that book, and decide for yourself if this is a worthy adaptation. There is no more doubt about it in my mind, as the interview seamlessly covers the “dry” chapters, and more, bringing a humanity that the original “digressions” sometimes lacked. The added layer of a self-aware adaptation through three different mediums (comic book, radio, theatre play), in a contemporary setting, in Paris, France, bring a different light to this work and makes it not just an adaptation of the Great Novel (which it does well), but a work of art in and out of itself, adding to the lasting legacy of the literary Leviathan.

To this Leviathan I leave the last word, much like the authors intended in their choice for the back cover attached in the next page.

Sail on.

[1] Last minute edit: maybe a day after typing this, as I looked again at Cosimo Miorelli’s website (http://www.cosimomiorelli.com/), I found a new entry entitled “Moby Dick City Blues”, a comic book collaboration in Italian. One glance at a couple illustrations was all it took: had it ordered within 10 minutes. I don’t even speak Italian. I swear I don’t have a problem, but I’d better stay away from Moby-Dick for a while if I don’t want that obsession to become one.

At least after I write a review of this new comic.

[2] The starting point could be Saint-Michel or Châtelet, whence the peregrination by the Seine and its picturesque ancient bookstalls is less direct and efficient, albeit indubitably more scenic. Artistic pursuit holds little space for efficiency.